To understand anal cancer, it’s first important to understand what cancer is: basically, the production of abnormal cells.

The body is programmed to routinely replenish cells in different organs. As normal cells age or get damaged, they die off. New cells take their place. This is what’s supposed to happen. Abnormal cell growth refers to a buildup of extra cells. This happens when:

- New cells form even though the body doesn’t need them or

- Old, damaged cells don’t die off.

These extra cells accumulate to form a tissue mass, lump, or growth called a tumor. These abnormal cells can destroy normal body tissue and spread through the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

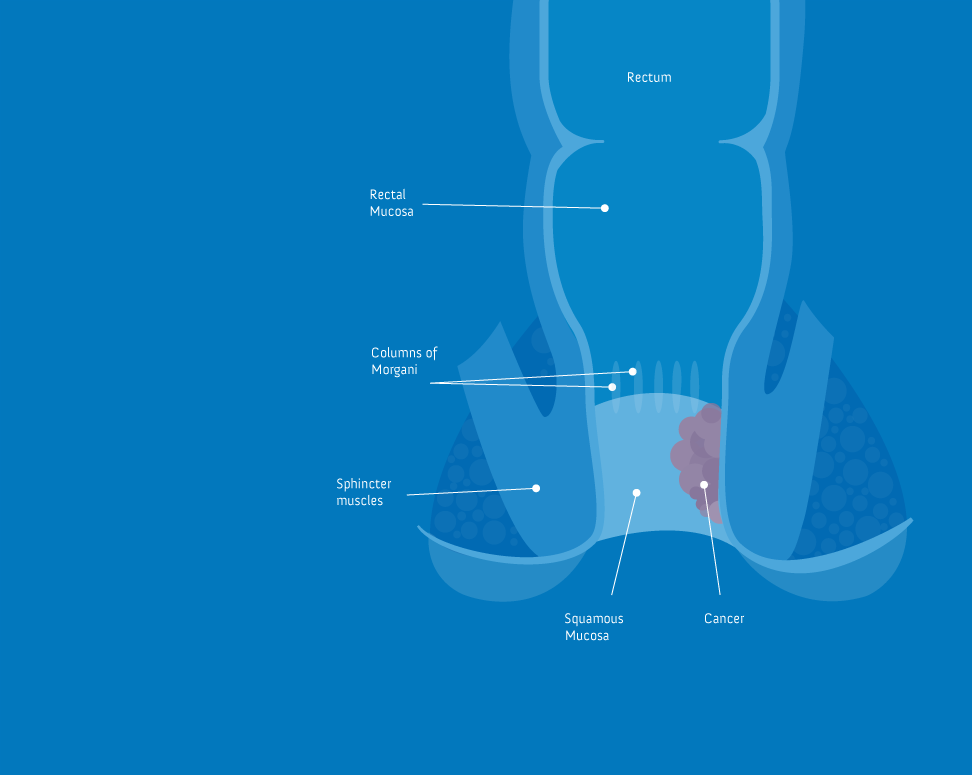

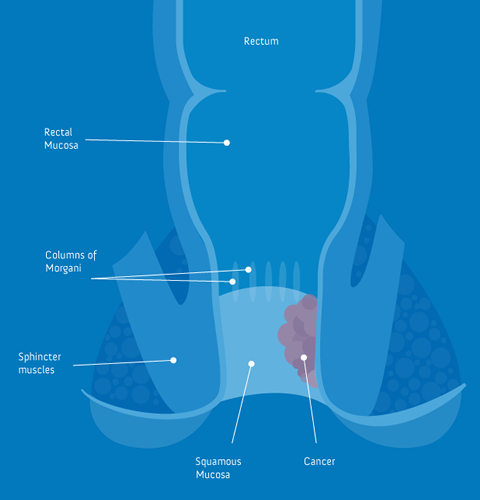

The anus is the opening of the rectum to the outside of the body where waste from food is passed.

Some growths in the anus start off as benign and can evolve into cancer over time. These growths are called precancerous. The condition is called dysplasia.

Benign means not cancerous. A benign tumor can get larger but does not spread to other tissues or organs.

Malignant means cancerous. A malignant tumor’s cells can invade nearby tissue and lymph nodes and then spread to other organs. These cells are destructive.

Benign tumors:

- Can be removed

- Usually don’t grow back

- Are rarely fatal

- Don’t spread to other tissues or body parts

Malignant tumors:

- Can often be removed

- Sometimes grow back

- Can invade other tissues and organs and cause damage

- Can spread to other body parts

- Can be fatal

There are 5 types of cancerous anal tumors:

- Carcinoma in situ

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Adenocarcinoma

- Skin cancer

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

Following is a description of each.

Carcinoma in situ: In this type of anal cancer, there are cells on the surface of the anus that look like cancer cells. However, they have not grown into the deeper layers of the anus. This condition is also called Bowen disease. This stage of anal cancer is really a pre-cancer or a very early stage.

Squamous cell carcinoma: This is the most common type of anal cancer. In this type of anal cancer, the tumors start in the squamous cells that line the lower part of the anus and the anal canal. Sometimes the tumors spread to the skin around the anus. This is called the perianal skin. If this happens, the tumors will be treated like skin cancers.

There is an area of the anus called the cloaca. One type of squamous cell cancer starts in that area. Like other squamous cell carcinomas, it is treated like skin cancer.

Adenocarcinomas: A few anal cancers start in cells that line the upper part of the anus. These are called adenocarcinomas. Paget disease is one type of adenocarcinoma that spreads through the surface layer of skin. It can affect the anal area. This is different from Paget disease of the bone.

Skin cancers: A small number of anal cancers are either

- basal cell carcinomas

- or melanomas.

Both of these are forms of skin cancer. Melanomas are more common on parts of your body that are exposed to sun. Most anal melanomas are hard to see or find. That’s why they’re usually found at a later stage.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): These are rare anal cancers. They are usually found in your stomach or small intestine. If they are found early, they can be removed with surgery. If they have spread, they can be treated with medications.

With Your Healthcare Team

When going through cancer treatment, your healthcare team is very important. Your healthcare team may include your oncologists, surgeon, nurse navigator, a dietitian, a social worker, or other medical professionals. Every member plays an important role. Use the tips below for talking with your healthcare team:

- Establish your main point of contact.

- Your main point of contact will probably be a nurse navigator, but it may be another member of your healthcare team. Who should you contact first with questions?

- You need to always be open and honest with your healthcare team about your physical and emotional well-being.

- Do not be afraid to ask questions.

- Cancer is usually not a medical emergency. There is time to ask your healthcare team any questions you may have, and to consider your treatment options.

- Write your questions down before your appointments. Take a pen and paper to write down the answers.

- Ask your doctor to write down your specific diagnosis.

Before beginning treatment, ask your healthcare team the following:

- What are all my treatment options?

- What are the long term and short term side effects of treatment, and how can I manage them?

- Will my fertility or ability to have children be affected?

- Am I eligible for clinical trials?

- If you develop any new problems or symptoms during treatment, tell your healthcare team immediately. You are not complaining. This is valuable information for your doctors.

- Do not change your diet, start an exercise program, or take any new medications, including vitamins and supplements, during treatment without talking to your healthcare team first.

With Your Caregiver

Your primary caregiver may be with you when you receive your diagnosis. Your primary caregiver may be your spouse, partner, adult child, parent, or friend. Your primary caregiver is the person who may come with you to appointments, take care of you after surgery or treatment, and support you throughout your cancer journey.

- Everyone reacts to the news of cancer differently. You may feel upset, shocked, or angry. It may take you some time to process the information. Your caregiver may or may not react the same way you do. Even if your caregiver does not react the same way you do, it does not mean that he or she does not care deeply.

- Establish your role and your caregiver’s role early. For example, will your caregiver be the one scheduling most of your appointments, or do you prefer to take an active role? Find what works best for you and your caregiver.

- Be open and honest with each other about how you both feel. Overly positive attitudes may hinder honest communication. It’s okay to be upset.

- Encourage your caregiver to take time to care for his or her own physical and emotional well-being. Being a caregiver comes with its own hardships.

- If your primary caregiver is your spouse or partner, your intimate and physical relationship may change.

With Your Children

Children are very perceptive, no matter their age. While you may wish to protect your children by not telling them about your diagnosis, even young children may be able to tell that something is wrong. Not knowing what is wrong may cause them more stress and anxiety. Here are some tips and general advice for talking to your children and teens about your cancer diagnosis:

- Wait until your emotions are under control and decide what to say ahead of time.

- Tell the truth and answer questions honestly. Depending on your children’s ages, it may not be appropriate to give them all the details, but do be truthful.

- Let them know what to expect. For example, let them know that after surgery you will need a lot of rest and may need to stay in the hospital. If your chemotherapy may cause you to lose your hair, let them know. Keep your children in the loop as much as possible.

- Explain to your children, especially younger children, that they cannot “catch” cancer.

- Let your children know that it is okay to cry or be upset. This may be especially important for your teens to hear.

- Tell teachers, babysitters, and others with responsibilities with and around your kids about your diagnosis in case they see behavior changes you may need to know about.

- Maintain normal schedules as much as possible.

- Let your kids help. Allow them to help with chores, and let them know that their help is important. Teens may want to take an active caregiver role. Let them do so, at appropriate levels.

- Look for support groups in your area. Many places offer support groups for children and teens whose parents have a cancer diagnosis.

- Know when to seek professional help. If your child begins to demonstrate unusual behavior such as angry outbursts, nightmares, or poor grades in school, ask your healthcare team for a recommendation for a counselor.

- For more specific guidance, speak with your nurse navigator who may have age-specific suggestions for how to communicate your diagnosis and treatment to your children.

With Family and Friends

You may choose to keep your cancer journey private, or you may choose to share your story with others. The choice is yours. Remember when family, friends, coworkers, or other acquaintances ask about your diagnosis, they are genuinely concerned about your well-being. You can share with them as much or as little information as you like. These suggestions may help you talk about your diagnosis:

- Decide how much information you want to share before you start telling people about your diagnosis.

- If you choose to keep your journey private, make sure to let people know that you appreciate their concern, but you hope they respect your privacy.

- Choose someone close to you, like your caregiver, to spread the word about updates and treatment progress. After a long day of treatment, you may not feel like calling and texting people, but your friends and family will probably want to know how you are.

- If you want to share your story, consider starting an email chain or a Facebook group.

- This way you can update everyone with one message instead of needing to answer a lot of emails and phone calls.

- You can also create your own private website at MyLifeLine.

- When people offer to help with things, let them. Your family and friends could cook dinner, drive you to an appointment, or babysit.

- If you lose your hair due to treatment or have visible surgical scars, strangers may ask about your diagnosis. Have a response prepared. Again, you may share as little or as much as you like.